General College Documents

The History of the Ulster College of Music

The Ulster College of Music was founded by Daphne Bell, a lecturer at Stranmillis College at the time, in 1966. The sixties were exciting years everywhere. This was the generation which produced some of the best risk-takers, problem solvers and inventors ever! In Belfast there was a cultural renaissance with many new initiatives taking off. With the inaugural Belfast Festival being held in 1962, cultural activity was on the rise in a way that 1950s Belfast could not have imagined. The Festival brought many international artists to the city, including Ravi Shankar. Poets of the 60s included Michael Longley, who wrote his first collection in 1969, No Continuing City, and Seamus Heaney, with his Belfast poems being mostly clustered in his collection Wintering Out.

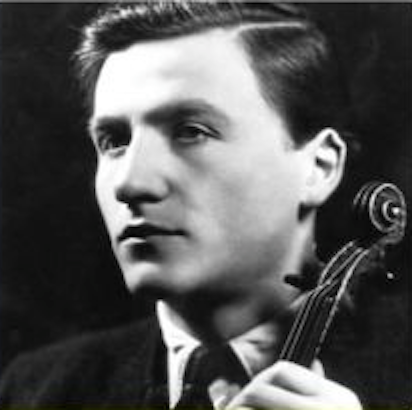

The Lyric Players Theatre was first established at Mary O’Malley’s house in Derryvolgie Avenue. Seeing herself as custodian of Northern Ireland’s cultural heritage, O’Malley sought to promote the arts in all their forms, simultaneously establishing a literary magazine, Irish crafts shop and art gallery and, together with Daphne Bell, an affiliate Academy of Music and Drama in connection with The Lyric. In 1965 the foundation stone for the first building of the Lyric Theatre was laid at the present site in Ridgeway Street. By the time the theatre moved there in 1966 the Arts Council of Northern Ireland with the help of conductor Maurice Miles had recruited a group of excellent musicians from Ireland (North and South) and the UK as well as many European countries, to found the new Ulster Orchestra. The object of the Council in forming the Orchestra was to bring the highest standards of music to every town in the Province. This was the first time that Ulster had had a fully professional orchestra ‘on the road’. The Ulster College of Music was founded in 1966 at the same time as the Ulster Orchestra and several of the orchestra’s musicians became the first tutors, including Janos Fürst, the leader of the orchestra, Brian Mack, principal violist, Maurice Meulien, principal cellist, Jozsef Racz, principal double bass player and Peter Eaton, principal clarinettist. Over the last 50 years many more musicians from the Ulster orchestra have taught at the Ulster College of Music, offering expert tuition to generations of students. Like the Ulster Orchestra the College was founded for the benefit of the whole of Ulster, and throughout its history students have been drawn from all over the province and even from the Republic of Ireland and further afield at times.

The first independent premises of the Ulster College of Music were in an old office building in Victoria Street, now demolished. From the beginning the College had a family atmosphere, where everybody was expected to lend a hand with anything. Miss Bell was very good at enthusing people for her ideals and she persuaded visiting professors to travel to Belfast, stay with College families and teach the most talented students, usually fortnightly. These include Derek Bell, harp, Hugh Tinney, piano, Mircea Petcu, violin, Pavel Crisan, violin, James Beck, horn, Judith Sheridan, voice, Robert Ehrlich, recorder, Sydney Sutcliffe, oboe and Jack Brymer, clarinet. Czech-born Professor Jaroslav Vanecek came to Belfast from Dublin once a month to teach at the College and his students included Paul Barritt and Fionnula Hunt, both internationally renowned violinists. A former student remembers Mrs Hunt dropping her daughter Fionnuala at her lesson and getting out the bucket to wash down the porch of the building, which was used as a makeshift toilet at night sometimes, leaving the premises rather unpleasant for the children arriving for their lessons.

The College was not only a centre of excellence in Music Education, but also a place where everyone with an interest in music could find the class, lesson, choir or ensemble to fulfil their needs, from young children to adults of all ages. The College still offers unique opportunities for adult students to learn an instrument, take part in other music classes and play in ensembles. The College continued to thrive during the 70s, although it was necessary to move to safer premises at 45 Windsor Avenue during the troubles. The College was first registered as a charity on 9 May 1968 and Her Royal Highness the Duchess of Kent became patron of the College in 1985. Daphne Bell was awarded an MBE for her services to music education in 1989. In 1992 Miss Bell and the carrying members of the College were able to secure the funds to buy the present building at 13 Windsor Avenue. The building at No.45 had become entirely unsuitable and was later demolished. The roof was leaking to such an extent, that water penetrated through two floors and into a grand piano! There were buckets everywhere and the volunteers were kept very busy.

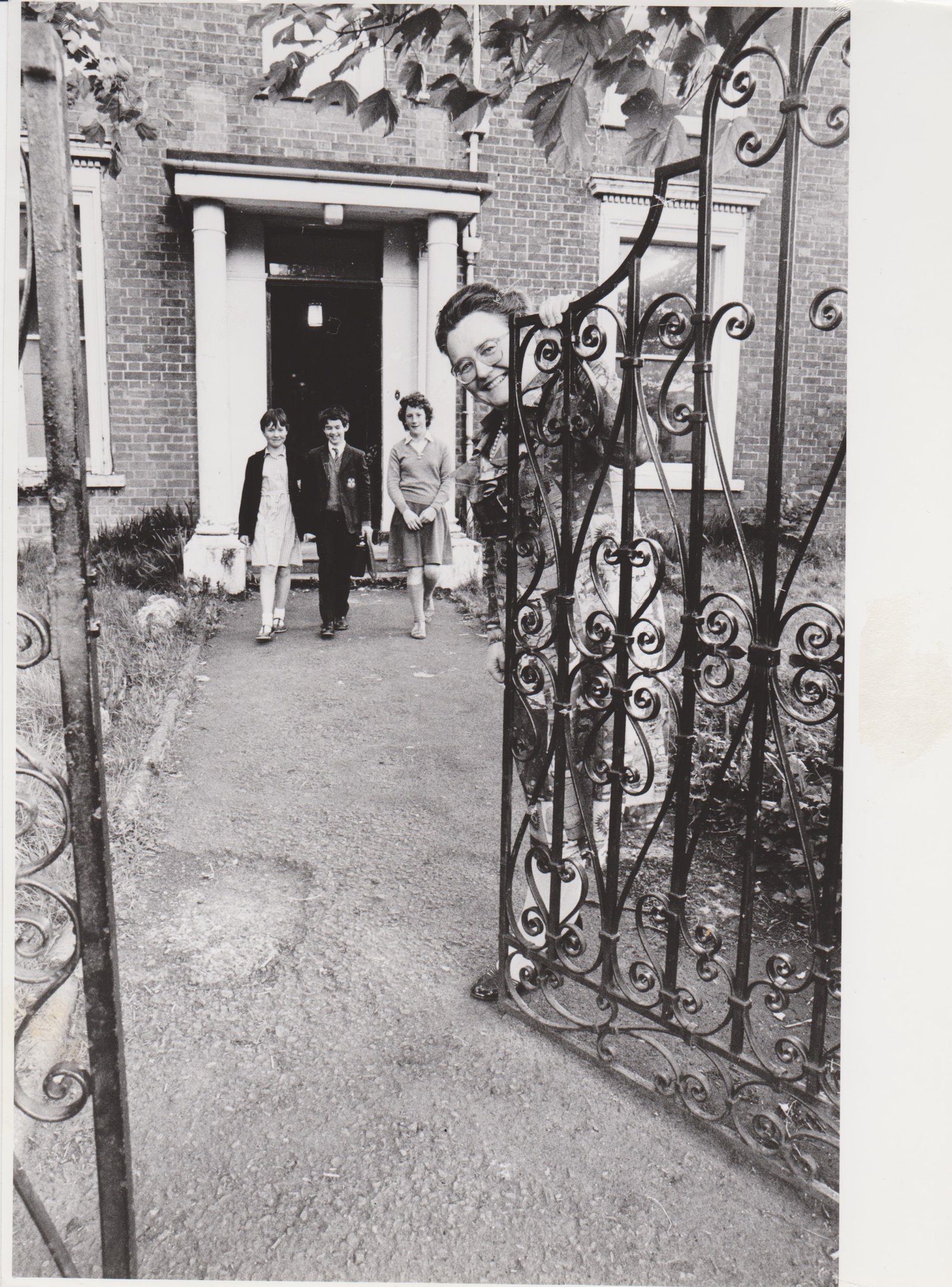

Miss Bell was very particular about good manners and proper attire. She kept a spare blue tie in the drawer for any professor who might turn up without a tie. She was herself easily recognised by her flowing capes and extravagant hats! Tea and coffee were always served to the professors and other important people. Miss Bell made it a condition for anyone taking lessons at the College (and their parents) to do their share of chores on the rota. One volunteer, who didn’t have a television set at home, was in a tricky situation one day when serving teas and one coffee to the Madrigal Group. One of their members was Sean Rafferty, and he was having the coffee, but the poor girl had never seen him…

There have been many changes over the years; students (and tutors) no longer use the blue College ties, which were once chosen as part of the College uniform which would be suitable for people from all backgrounds. There is no longer a compulsory rota of chores to be done by every member. But the friendly family atmosphere remains, and many parents, students and tutors put in hours of voluntary work when they can. The building is filled with music every day in term time and children continue to acquire a love of music.

Many former students have become professional musicians. Many more have become keen amateur musicians. One former classical guitar student loved his lessons with Jim McCullagh and was very sad, when his teacher had to leave the College due to ill health. He remembers playing his farewell recital at the Ulster College of Music before going away to university. Just before the end of the recital Jim McCullough came in, having been told the wrong time for the recital. So the student just played it all again for his favourite teacher and friend. Another student, who was a talented pianist, achieving a diploma at the age of 15, remembers the friendly theory teacher, who once allowed the class to watch the rugby world cup, leaving that week’s theory to be done at home! On the other hand a student, who admired the sounds coming from the room where Jennifer Sturgeon (now in the Ulster Orchestra) had her flute lesson, was told by Miss Bell not to tell her, in case she stopped practising.

The Ulster College of Music continues to offer tuition on all orchestral instruments as well as Suzuki Violin, Piano, Recorder, Voice, Drama, Guitar, Irish Traditional Instruments, Theory, Ensembles, Music Appreciation, GCSE and As/A level and a Musical Fun Foundation Course for children.

Daphne Bell (1926-2006)

A personal reflection on the life of the late Miss Daphne Bell MBE

by Dr Joe McKee Principal, City of Belfast School of Music

Tribute To A Champion of Music

News Letter 27.02.2006

The musical community in Ireland has lost a larger than life character with the death of Daphne Bell. Known universally to thousands of young musicians and their nervously deferential parents as “Miss Bell”, Daphne Bell was a lifelong and tireless champion of high standards in music. Born in Dublin on July 11, 1926, the daughter of a leading auctioneer in the city, she quickly acquired her parents’ love of things of beauty, not least silver. Her elegant home in Stranmillis, overlooking the Botanic Gardens, was a treasury of fine furniture, interesting paintings and numerous other objets d’art.

The musical community in Ireland has lost a larger than life character with the death of Daphne Bell. Known universally to thousands of young musicians and their nervously deferential parents as “Miss Bell”, Daphne Bell was a lifelong and tireless champion of high standards in music. Born in Dublin on July 11, 1926, the daughter of a leading auctioneer in the city, she quickly acquired her parents’ love of things of beauty, not least silver. Her elegant home in Stranmillis, overlooking the Botanic Gardens, was a treasury of fine furniture, interesting paintings and numerous other objets d’art.

She followed her heart into music, however, realising that her gifts lay in teaching rather than performance. In her early career she taught in Armagh Girls High School and Friends School, Lisburn, before joining the staff at Ashfield Girls School in Belfast in the mid 1950s. Her years at Ashfield were amongst the happiest in her life and her experiences there were to stand her in good stead when she moved to Stranmillis College as a lecturer in Music in 1966, retiring as a Senior Lecturer in 1984.

In the 70s and 80s when initial teacher training was more hands-on and less academic, Miss Bell was an inspiring and colourful role model for her students. Those unfortunate individuals who arrived at Miss Bell’s room without their descant recorders quickly learned that rather than being excused class they were expected to play along silently on rulers which were kept for the purpose. Miss Bell never gladly suffered fools.

Remembered by generations of Stranmillis staff and students for her big hats and theatrical cloaks, Daphne Bell cut an imposing figure, but her greatest grass roots legacy is the Ulster College of Music. She set it up as a privately funded centre of excellence for instrumental teaching in Northern Ireland. In its heyday the UCM attracted teachers of the highest calibre, described by its founder as visiting professors, who achieved very creditable results with a host of highly talented young musicians. In the 1970s, in particular, the Ulster College of Music was producing regular players for the National Youth Orchestra of Great Britain.

The Ulster Junior Orchestra, another Bell spin-off from the UCM, did exceptional work in summer residences. For this, top UK musicians of the standing of Sydney Sutcliffe, Jack Brymer and others were persuaded to travel to Northern Ireland to create a fully professional environment to nurture local talent. All of this was achieved on a shoe-string, and at a difficult time when very few visitors were coming to Ulster, the majority of the participants simply being swept along by Daphne Bell’s vision and irrepressible energy. As well as calling on the support of influential friends such as Dame Ruth Railton and Lord King, Bell had that special gift of being able to persuade large numbers of volunteers to work tirelessly for a common goal.

Individuals with big personalities do great things, but they can also create waves which have the potential to sink the ship. In her retirement, Daphne Bell found control of her beloved Ulster College slipping away from her, a situation which caused her great personal anguish. She had no immediate family, so her last years were enlivened by a small number of close friends whose visits kept her abreast of local music gossip.

Daphne Bell was a big-hearted generous woman who gave selflessly of her time and talents. She will be greatly missed by numerous professional musicians who owe everything to her early advice and guidance, but by many thousands of others who were simply lucky enough to be touched by her warm humanity.

Teacher; College Administrator

The Dictionary of Ulster Biography

A detailed article about Miss Daphne Bell by Richard Froggatt

Daphne Bell throughout her career was in post as a music teacher, but she had a notable spare-time activity in the musical life of Ulster: practically single-handedly she founded, and for years directed, the Ulster College of Music in Belfast. (She was in fact officially Honorary Director and gave her services for no fee or other income.)

Daphne Bell throughout her career was in post as a music teacher, but she had a notable spare-time activity in the musical life of Ulster: practically single-handedly she founded, and for years directed, the Ulster College of Music in Belfast. (She was in fact officially Honorary Director and gave her services for no fee or other income.)

She was born at St Stephen’s Green, Dublin. Her father, an auctioneer, and mother were Quakers; this being so, Daphne was sent as a boarder to Friends’ School, Lisburn, County Antrim. Rather than pursue a career as an executant musician, she became a teacher, first at schools – Armagh Girls’ High School, Friends’ School, and Ashfield Girls High School in east Belfast. At Ashfield, she insisted that prefects wear distinctive blue stockings, so that they would recognisable at a distance even in the foulest weather. In 1966 she took up a post as Lecturer at Stranmillis College, Belfast (the teacher training college, now Stranmillis University College). She remained there until retirement in 1984 as Senior Lecturer. This was in a real sense her “day job”, which she carried out until retirement in 1983.

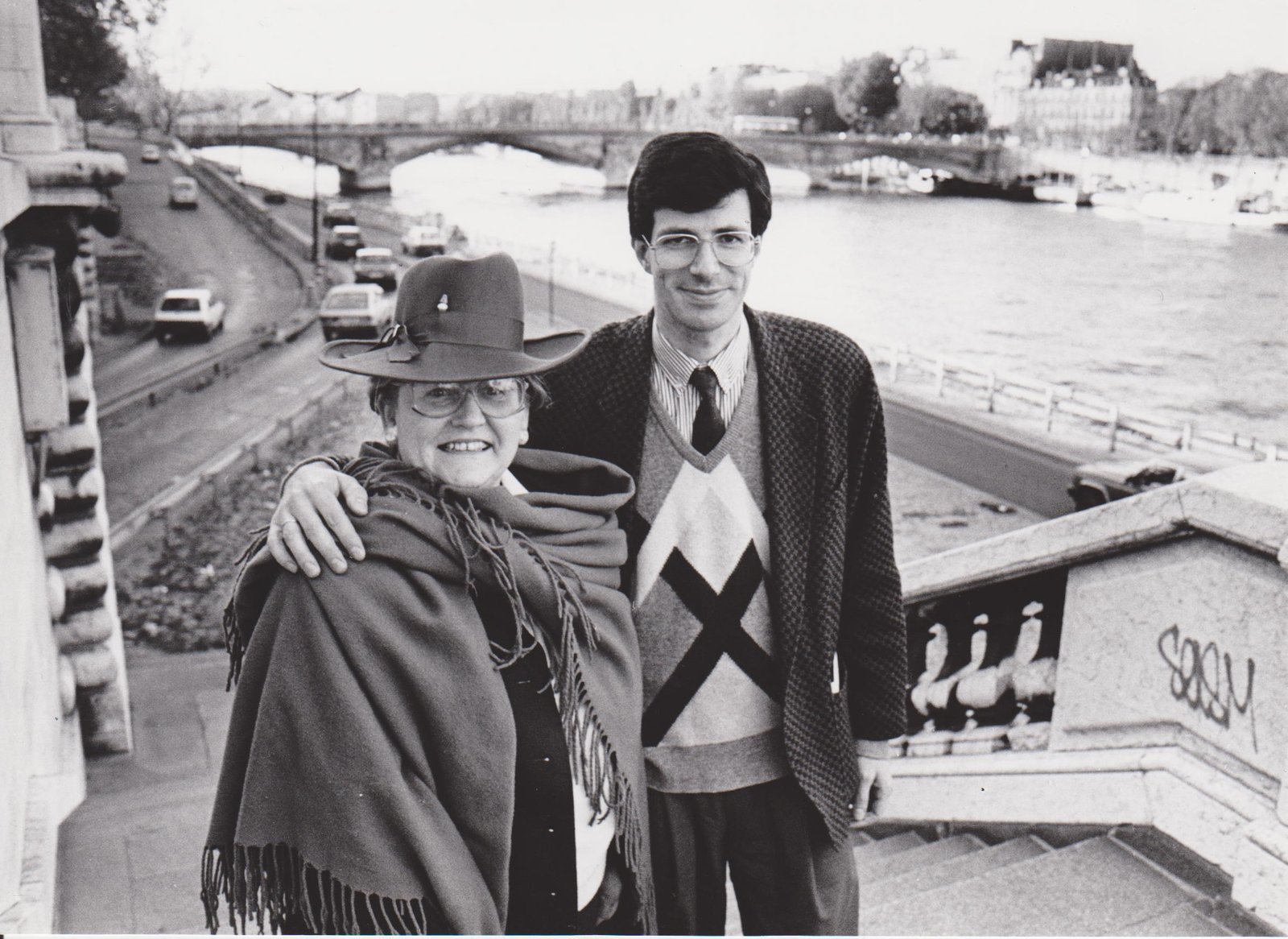

Meanwhile, evenings and weekends, she devoted her considerable energy and commitment to founding the Ulster College of Music. Her aim was to create a privately-funded centre for excellence in teaching music (not necessarily “classical” music). One of her first steps was to secure a distinguished patron, which she did: Dame Ruth Railton, the founder and music director for nearly 20 years of the National Youth Orchestra of Great Britain. Dame Ruth was described by Daphne Bell as a tremendous example and inspiration; Daphne described her as “The Great Dame Ruth”. Also from the beginning the College benefited from the support of the outstanding violinist and teacher Jaroslav Vanecek. One later associate of the College and neighbour of Daphne Bell near Queen’s University, described things this way: “There was an astonishing woman called Daphne Bell, who ran the Ulster College of Music on absolutely nothing — no grants, borrowed instruments, teachers whom she coaxed into working for an absolute pittance.” The teachers included members of the Ulster Orchestra, and others who would travel to Belfast especially to give lessons; no big fee, and either a “cross-channel” or a cross-border journey, not to mention the constant shadow of the Troubles. There was one compensation though: the accolade of being described as “visiting professors”.

Closely linked to the College was the Ulster Junior Orchestra, and similarly, some of the internationally-acclaimed musicians who were persuaded to come to Belfast, among them oboist Sidney Sutcliffe and clarinettist Jack Brymer. When she organised masterclasses, only the best would do; for an all-day session of individual masterclasses for oboe students, Evelyn Barbirolli, not just a distinguished instrumentalist herself but who was the wife of legendary conductor Sir John Barbirolli, was only too pleased to take them. Moreover, no hotel accommodation for these distinguished visitors: they were hosted in the homes of friends of the College and students’ parents, who also functioned as transport providers.

It is also worth pointing out that, in a province with a “segregated” schools system – that is, for whatever reasons, the school-age attend different schools effectively according to religion – the College was non-denominational in every sense. Daphne Bell if asked questions on this theme would dismiss them, explaining that being a Quaker she was neither protestant nor catholic, and was from Dublin so not really understand, and was not interested anyway as it had nothing to do with music. (Her Quaker background was not merely that; she was always very concerned for the bereaved which she said was how she was brought up. She occasionally attended Meeting, and legend has it that she did not always speak then.) The entrance test was tough on weeding out the tone-deaf; the only thing to be confessed to was undermotivation. There was no uniform of any kind except, for public performances such as the College Annual Recital, a pullover of a light blue colour, which she chose, she explained, as it was the only colour which could not offend anyone; she seemed rather baffled how important colours could be in Ulster. (She also seemed surprised when it was pointed out to her that blue watered silk was the colour of the Knights of St Patrick.)

Daphne Bell was perpetually described as “larger than life”, a “big personality”, and such. She was addressed as “Miss Bell”, and while being allowed to address her as “Daphne” was something of a privilege, everyone referred to her as that anyway; and if not, as “Dame” Daphne, a reference to her presence more than to her MBE, awarded in 1989 for services to music in Ulster. Countless students still recall her weekly theory classes, in which the large room was filled with students busily (mostly) completing exercises in keys, scales, relative minors and other musical points. Her sartorial presence was also noteworthy; an energetic figure in cape and wide-brimmed hat was easily recognisable at any distance (as was her near-next-door neighbour Michael Barnes, Director of the Belfast Festival at Queen’s; though while both were dedicated to the Arts in their different ways, so were they recognisable figures round town, though for opposite sartorial reasons). She was even to make an appearance in a social column of a well-known London newspaper: at a music conference, delegates relaxed by playing table tennis. “Dame” Daphne, it was reported, was a formidable player, especially with one hand keeping her impressive headwear firmly in place.

Latterly, certain developments in the organisation of education in Ulster effectively acted against Daphne Bell personally, though even she would have admitted that not everyone goes on forever, and indeed, she was beginning to suffer bouts of ill health, eventually having to leave her beloved Belfast home (full of various objets d’art which reflected, said friends, her father’s expertise) for a nursing home and latterly, hospital. At her committal were numerous of her former students and many others; music was performed by some of the many College “graduates” to have become musicians at the highest international levels. A close associate and friend said of her: “Though many acknowledged she could be a rather formidable presence, no-one doubted that she was motivated at all times by her concern for the well-being of the College, which she conceived as a place of learning, never an end of itself.” Daphne Bell was often asked the secret of her success; by musicians, parents (though as there were students of all ages this category was not unrestricted), examiners, dignitaries, whomever. Her stock reply was: “By surrounding myself with excellent people of course!”